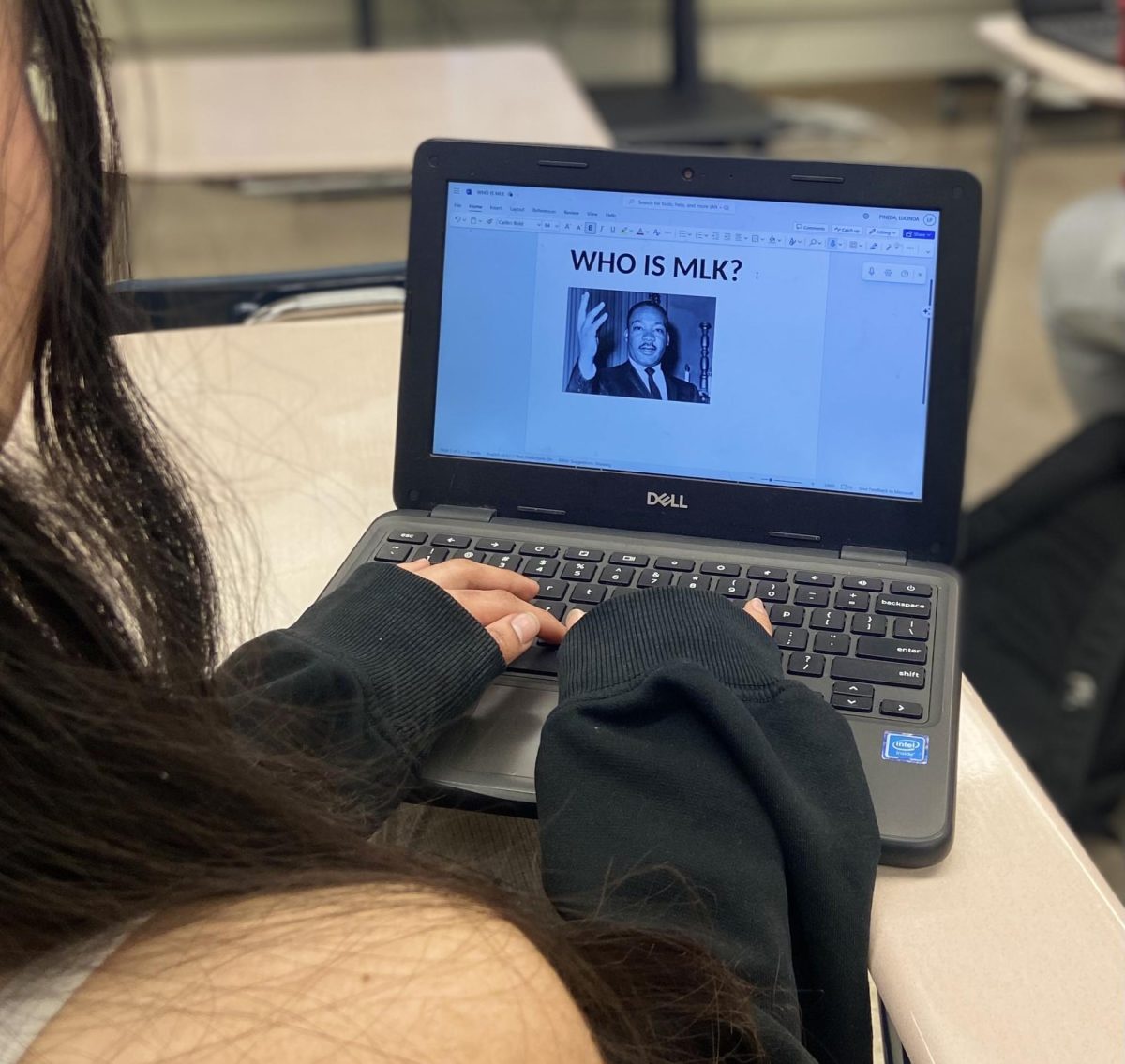

In light of Martin Luther King Junior Day, American schools take different approaches in honoring this national holiday, but the imperative question still needs to be asked: Are schools doing enough to impart crucial comprehension of African American history?

State-wide educational curriculums vary based on what they decide to teach for up and coming African American holidays and annually recognized months like Juneteenth, Black History Month, and of course, Martin Luther King Junior day. But the eminent issue of schools improperly teaching students about African American history still arises.

“…I feel like we could do more stuff but I do think the school is trying by having things like Black Student Alliance and ethnic studies..” reported Kennedy junior Stephanie Doroteo.

So how are other schools incorporating African American history into their curriculum? Besides granting students the day off, many schools may briefly discuss the more conspicuous and commonly talked about events like King’s famous “I Have A Dream” speech, Harriet Tubman, or the Civil War. However, this national day should be taking the opportunity to tell the real stories surrounding African American history, apart from the expected state standards.

Schools fail to go in depth about African American historical moments, tending to prioritize white narrative in history lessons. For example, the role of Black soldiers within the American Revolution is often trivialized with white figures like George Washintong or Ulysses Grant being the center of lessons. This in turn takes away from the reality that African American men made up the majority of the army. Militia enlisted men like Prince Dunsick, Titus Cobum, and Caesar Ferrit, to name a few, were still enslaved while helping lead great victories in the war.

This is not to say the problem lies within all teachers not caring to examine the true history of African American studies. In actuality, the problem continues to occur because many laws enforced by the U.S. states’ Board of Education and government haven’t given teachers the chance to do so.

As early as July of 2022, Virginia had passed laws omitting teaching Martin Luther King Jr. topics (GRS’55, Hon.’59) from their first drafts of their new K-12 social studies curriculum. Jefferey Sach, a researcher for PEN America, reported 35 states passing 137 bills limiting what schools can teach about race, American history, gender identity, sexual orientation, and politics.

Within that same year during the month of November, up to 16 states restricted what educators could teach about race and ethnicity as stated by the Temple University Center for Public Health Law Research. Educators have noted this as prohibiting using “critical race theory”, a topic of controversy within recent years.

Since January 2021, eleven states have passed House Bills that ultimately ban teaching critical race theory while 44 more have introduced bills or plan to enact them in the next session. Some schools have taken the extent of this opportunity to ban teaching Martin Luther King to their students as a way to not cause discomfort for their white peers.

CRT provides the point of view of African Americans, showing the systemic racism that is still present and seeing its effects throughout history. CRT has been used to teach and help students understand what was actually happening during critical time periods. Not only that, but it has also been the basis for the formation of newer courses like African American or ethnic studies. Without critical race theory, educators won’t be able to teach to the full extent, which continues to present itself as the common issue

Similarly, printed textbooks relied on by teachers often undermine the reality that African Americans went through by not disclosing certain events or misconstruing historical accounts. White figures like George Washington or Thomas Jefferson, and several other presidents, have rarely been mentioned in text to have owned enslaved people. Words like “African workers” or “aliens” can be seen at various times in social studies textbooks that hide such deliberate racist connotations.

Ultimately, teachers are left on their own to analyze the discourse of these time periods, which doesn’t allow them to give an adequate lesson plan. High schoolers get the short end of the stick while many students may not even get to learn these more important events as they may or may not be taking a history class this year. This further induces the lack of information spread about black history because they don’t even get the chance to learn about it, further staggering these statistics

While California has been recognized as having a more progressive front to educating fellow students on such history topics, arguably, improvements within California can still be made.

California teachers don’t get the needed training in order to dive into topics of true Black history; credentials for teaching things like English or math are monitored but African American studies are not.

Up until 2016, the California Board of Education did not make teaching events and historical figures such as Jackie Jobinson, Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, and the discussion of slavery and its effect on the Constitution mandatory within elementary schools. Even then, it’s only until eleventh grade that students get more involved in more detailed records in African American history like Plessy vs. Ferguson on Reconstruction and its effect on freed slaves.

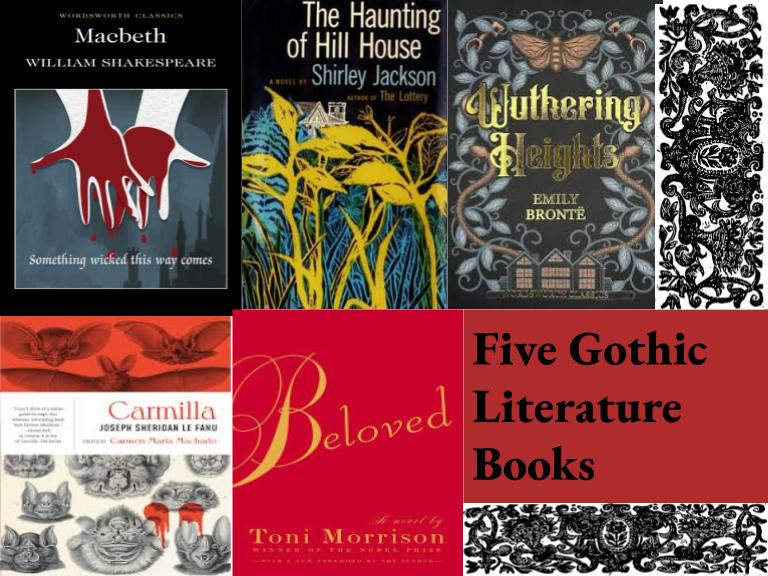

As reformed as California may be, one thing they could learn from fellow schools like Louisiana or Philadelphia is making African American history a graduating requirement or offering African American studies as an AP course. In this course, students are able to embark on early documents of slaves and their stories, not the tainted versions taught in modern history books.

What’s more important is learning to engage students in learning about African American history by promoting it across campus, enabling them to actually learn and not have to just sit through a lecture in class while information goes in and out one ear.

While the famous “I Have a Dream” speech may be brought up, many teachers overlook King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail or “Beyond Vietnam – A Time to Break Silence.” These accounts don’t just paint King as a peaceful character as many might want to believe he is; they shed light on the true fights he had to endure as well as his resilience.

Although some may argue that the introduction of newer courses like African American studies, ethnic students, and the deeper involvement around black history during Black History month shows signs that the country does care about involving students in this topic. This only shows small steps as it has only more recently been implemented in fewer more leftist states, where many states like Florida, for example, have prohibited teaching these things.

This also doesn’t account for the fact that it has only become a recent implementation while African American history has been around for as long as time. But the more recent introduction may not even do much as only eight percent of seniors are able to identify slavery as the cause of the civil war.

Here at Kennedy High School, African American studies are only offered as an additional college class, for example, not a required one. Kennedy also does not make it a mandatory graduating requirement as some states do. While ethnic studies is also offered, inaugurally, as of 2030 is it then going to be a mandatory requirement.

Similarly, workshops like navigating black history and identity could be offered along with the ELA or mental health workshops that are given. The campus notably unifies its students by giving Hispanic celebrated activities like Banda night or Folklorico dances, but may not be fully inclusive by presenting more African American related cultural activities for students to celebrate.

Including so-called “controversial” topics of African American history provides more inclusivity among students and allows young black students to confront racial injustice and know what is truly going on. This allows for events like the murders of George Floyd or Breonna Taylor to not be swept under the rug and be accounted for. Additionally, African American students would be able to understand their culture and identity through these lessons as well.

Having a restricted curriculum doesn’t give the support that students need to face the world. All students would know how to take action against inequality that is still happening now, if schools took the step to include more of these topics, creating an improved tomorrow rather than moving backwards.